Introduction to Groups and Communicators

Author: Wesley BlandIn all previous tutorials, we have used the communicator MPI_COMM_WORLD. For simple applications, this is sufficient as we have a relatively small number of processes and we usually either want to talk to one of them at a time or all of them at a time. When applications start to get bigger, this becomes less practical and we may only want to talk to a few processes at once. In this lesson, we show how to create new communicators to communicate with a subset of the original group of processes at once.

Note - All of the code for this site is on GitHub. This tutorial’s code is under tutorials/introduction-to-groups-and-communicators/code.

Overview of communicators

As we have seen when learning about collective routines, MPI allows you to talk to all processes in a communicator at once to do things like distribute data from one process to many processes using MPI_Scatter or perform a data reduction using MPI_Reduce. However, up to now, we have only used the default communicator, MPI_COMM_WORLD.

For simple applications, it’s not unusual to do everything using MPI_COMM_WORLD, but for more complex use cases, it might be helpful to have more communicators. An example might be if you wanted to perform calculations on a subset of the processes in a grid. For instance, all processes in each row might want to sum a value. This brings us to the first and most common function used to create new communicators:

MPI_Comm_split(

MPI_Comm comm,

int color,

int key,

MPI_Comm* newcomm)

As the name implies, MPI_Comm_split creates new communicators by “splitting” a communicator into a group of sub-communicators based on the input values color and key. It’s important to note here that the original communicator doesn’t go away, but a new communicator is created on each process. The first argument, comm, is the communicator that will be used as the basis for the new communicators. This could be MPI_COMM_WORLD, but it could be any other communicator as well. The second argument, color, determines to which new communicator each processes will belong. All processes which pass in the same value for color are assigned to the same communicator. If the color is MPI_UNDEFINED, that process won’t be included in any of the new communicators. The third argument, key, determines the ordering (rank) within each new communicator. The process which passes in the smallest value for key will be rank 0, the next smallest will be rank 1, and so on. If there is a tie, the process that had the lower rank in the original communicator will be first. The final argument, newcomm is how MPI returns the new communicator back to the user.

Example of using multiple communicators

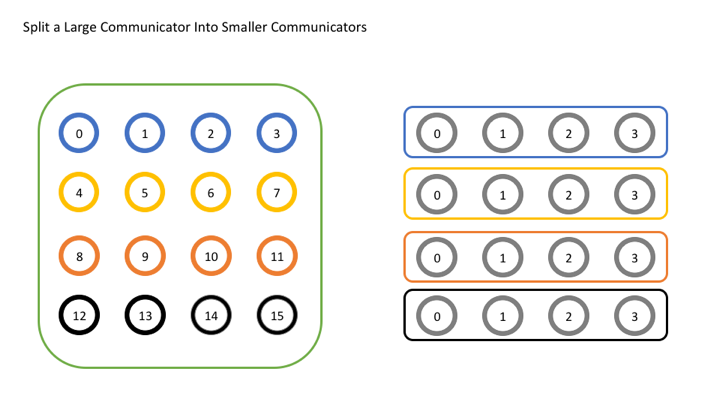

Now let’s look at a simple example where we attempt to split a single global communicator into a set of smaller communicators. In this example, we’ll imagine that we’ve logically laid out our original communicator into a 4x4 grid of 16 processes and we want to divide the grid by row. To do this, each row will get its own color. In the image below, you can see how each group of processes with the same color on the left ends up in its own communicator on the right.

Let’s look at the code for this.

// Get the rank and size in the original communicator

int world_rank, world_size;

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &world_rank);

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &world_size);

int color = world_rank / 4; // Determine color based on row

// Split the communicator based on the color and use the

// original rank for ordering

MPI_Comm row_comm;

MPI_Comm_split(MPI_COMM_WORLD, color, world_rank, &row_comm);

int row_rank, row_size;

MPI_Comm_rank(row_comm, &row_rank);

MPI_Comm_size(row_comm, &row_size);

printf("WORLD RANK/SIZE: %d/%d \t ROW RANK/SIZE: %d/%d\n",

world_rank, world_size, row_rank, row_size);

MPI_Comm_free(&row_comm);

The first few lines get the rank and size for the original communicator, MPI_COMM_WORLD. The next line does the important operation of determining the “color” of the local process. Remember that color decides to which communicator the process will belong after the split. Next, we see the all important split operation. The new thing here is that we’re using the original rank (world_rank) as the key for the split operation. Since we want all of the processes in the new communicator to be in the same order that they were in the original communicator, using the original rank value makes the most sense here as it will already be ordered correctly. After that, we print out the new rank and size just to make sure it works. Your output should look something like this:

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 0/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 0/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 1/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 1/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 2/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 2/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 3/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 3/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 4/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 0/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 5/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 1/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 6/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 2/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 7/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 3/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 8/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 0/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 9/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 1/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 10/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 2/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 11/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 3/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 12/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 0/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 13/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 1/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 14/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 2/4

WORLD RANK/SIZE: 15/16 ROW RANK/SIZE: 3/4

Don’t be alarmed if yours isn’t in the right order. When you print things out in an MPI program, each process has to send its output back to the place where you launched your MPI job before it can be printed to the screen. This tends to mean that the ordering gets jumbled so you can’t ever assume that just because you print things in a specific rank order, that the output will actually end up in the same order you expect. The output was just rearranged here to look nice.

Finally, we free the communicator with MPI_Comm_free. This seems like it’s not an important step, but it’s just as important as freeing your memory when you’re done with it in any other program. When an MPI object will no longer be used, it should be freed so it can be reused later. MPI has a limited number of objects that it can create at a time and not freeing your objects could result in a runtime error if MPI runs out of allocatable objects.

Other communicator creation functions

While MPI_Comm_split is the most common communicator creation function, there are many others. MPI_Comm_dup is the most basic and creates a duplicate of a communicator. It may seem odd that there would exist a function that only creates a copy, but this is very useful for applications which use libraries to perform specialized functions, such as mathematical libraries. In these kinds of applications, it’s important that user codes and library codes do not interfere with each other. To avoid this, the first thing every application should do is to create a duplicate of MPI_COMM_WORLD, which will avoid the problem of other libraries also using MPI_COMM_WORLD. The libraries themselves should also make duplicates of MPI_COMM_WORLD to avoid the same problem.

Another function is MPI_Comm_create. At first glance, this function looks very similar to MPI_Comm_create_group. Its signature is almost identical:

MPI_Comm_create(

MPI_Comm comm,

MPI_Group group,

MPI_Comm* newcomm)

The key difference however (besides the lack of the tag argument), is that MPI_Comm_create_group is only collective over the group of processes contained in group, where MPI_Comm_create is collective over every process in comm. This is an important distinction as the size of communicators grows very large. If trying to create a subset of MPI_COMM_WORLD when running with 1,000,000 processes, it’s important to perform the operation with as few processes as possible as the collective becomes very expensive at large sizes.

There are other more advanced features of communicators that we do not cover here, such as the differences between inter-communicators and intra-communicators and other advanced communicator creation functions. These are only used in very specific kinds of applications which may be covered in a future tutorial.

Overview of groups

While MPI_Comm_split is the simplest way to create a new communicator, it isn’t the only way to do so. There are more flexible ways to create communicators, but they use a new kind of MPI object, MPI_Group. Before going into lots of detail about groups, let’s look a little more at what a communicator actually is. Internally, MPI has to keep up with (among other things) two major parts of a communicator, the context (or ID) that differentiates one communicator from another and the group of processes contained by the communicator. The context is what prevents an operation on one communicator from matching with a similar operation on another communicator. MPI keeps an ID for each communicator internally to prevent the mixups. The group is a little simpler to understand since it is just the set of all processes in the communicator. For MPI_COMM_WORLD, this is all of the processes that were started by mpiexec. For other communicators, the group will be different. In the example code above, the group is all of the processes which passed in the same color to MPI_Comm_split.

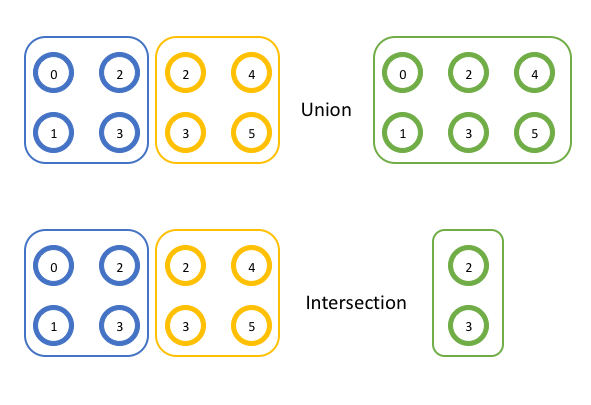

MPI uses these groups in the same way that set theory generally works. You don’t have to be familiar with all of set theory to understand things, but it’s helpful to know what two operations mean. Here, instead of referring to “sets”, we’ll use the term “groups” as it applies to MPI. First, the union operation creates a new, (potentially) bigger set from two other sets. The new set includes all of the members of the first two sets (without duplicates). Second, the intersection operation creates a new, (potentially) smaller set from two other sets. The new set includes all of the members that are present in both of the original sets. You can see examples of both of these operations graphically below.

In the first example, the union of the two groups {0, 1, 2, 3} and {2, 3, 4, 5} is {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5} because each of those items appears in each group. In the second example, the intersection of the two groups {0, 1, 2, 3}, and {2, 3, 4, 5} is {2, 3} because only those items appear in each group.

Using MPI groups

Now that we understand the fundamentals of how groups work, let’s see how they can be applied to MPI operations. In MPI, it’s easy to get the group of processes in a communicator with the API call, MPI_Comm_group.

MPI_Comm_group(

MPI_Comm comm,

MPI_Group* group)

As mentioned above, a communicator contains a context, or ID, and a group. Calling MPI_Comm_group gets a reference to that group object. The group object works the same way as a communicator object except that you can’t use it to communicate with other ranks (because it doesn’t have that context attached). You can still get the rank and size for the group (MPI_Group_rank and MPI_Group_size, respectively). However, what you can do with groups that you can’t do with communicators is use it to construct new groups locally. It’s important to remember here the difference between a local operation and a remote one. A remote operation involves communication with other ranks where a local operation does not. Creating a new communicator is a remote operation because all processes need to decide on the same context and group, where creating a group is local because it isn’t used for communication and therefore doesn’t need to have the same context for each process. You can manipulate a group all you like without performing any communication at all.

Once you have a group or two, performing operations on them is straightforward. Getting the union looks like this:

MPI_Group_union(

MPI_Group group1,

MPI_Group group2,

MPI_Group* newgroup)

And you can probably guess that the intersection looks like this:

MPI_Group_intersection(

MPI_Group group1,

MPI_Group group2,

MPI_Group* newgroup)

In both cases, the operation is performed on group1 and group2 and the result is stored in newgroup.

There are many uses of groups in MPI. You can compare groups to see if they are the same, subtract one group from another, exclude specific ranks from a group, or use a group to translate the ranks of one group to another group. However, one of the recent additions to MPI that tends to be most useful is MPI_Comm_create_group. This is a function to create a new communicator, but instead of doing calculations on the fly to decide the makeup, like MPI_Comm_split, this function takes an MPI_Group object and creates a new communicator that has all of the same processes as the group.

MPI_Comm_create_group(

MPI_Comm comm,

MPI_Group group,

int tag,

MPI_Comm* newcomm)

Example of using groups

Let’s look at a quick example of what using groups looks like. Here, we’ll use another new function which allows you to pick specific ranks in a group and construct a new group containing only those ranks, MPI_Group_incl.

MPI_Group_incl(

MPI_Group group,

int n,

const int ranks[],

MPI_Group* newgroup)

With this function, newgroup contains the processes in group with ranks contained in ranks, which is of size n. Want to see how that works? Let’s try creating a communicator which contains the prime ranks from MPI_COMM_WORLD.

// Get the rank and size in the original communicator

int world_rank, world_size;

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &world_rank);

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &world_size);

// Get the group of processes in MPI_COMM_WORLD

MPI_Group world_group;

MPI_Comm_group(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &world_group);

int n = 7;

const int ranks[7] = {1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13};

// Construct a group containing all of the prime ranks in world_group

MPI_Group prime_group;

MPI_Group_incl(world_group, 7, ranks, &prime_group);

// Create a new communicator based on the group

MPI_Comm prime_comm;

MPI_Comm_create_group(MPI_COMM_WORLD, prime_group, 0, &prime_comm);

int prime_rank = -1, prime_size = -1;

// If this rank isn't in the new communicator, it will be

// MPI_COMM_NULL. Using MPI_COMM_NULL for MPI_Comm_rank or

// MPI_Comm_size is erroneous

if (MPI_COMM_NULL != prime_comm) {

MPI_Comm_rank(prime_comm, &prime_rank);

MPI_Comm_size(prime_comm, &prime_size);

}

printf("WORLD RANK/SIZE: %d/%d \t PRIME RANK/SIZE: %d/%d\n",

world_rank, world_size, prime_rank, prime_size);

MPI_Group_free(&world_group);

MPI_Group_free(&prime_group);

MPI_Comm_free(&prime_comm);

In this example, we construct a communicator by selecting only the prime ranks in MPI_COMM_WORLD. This is done with MPI_Group_incl and results in prime_group. Next, we pass that group to MPI_Comm_create_group to create prime_comm. At the end, we have to be careful to not use prime_comm on processes which don’t have it, therefore we check to ensure that the communicator is not MPI_COMM_NULL, which is returned from MPI_Comm_create_group on the ranks not included in ranks.